Matthew 28:1-10

April 20

David A. Davis

Jump to audio

It starts with a “great earthquake”. The resurrection morning, according to Luke, begins with the earth shaking at sunrise as the women are on their way to see the tomb. Perhaps the earthquake was the divine tool used by the descending angel to roll the stone away from the entrance to the tomb. The angel’s countenance and attire has quite a glow. So startling that those guarding the tomb are scared to death. Like most angels in the bible, the radiant one perched on the rock tells the women not to be afraid. The angel goes on to explain that the crucified one they are looking for was not there, for “he had been raised, as he said.” The women are invited in to see where the body had been. “He is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him.” The women leave quickly with “fear and great joy” to run and tell the disciples. It must not have been far from the tomb when the Risen Jesus suddenly appears and says, “Greetings!”

You will remember that when the angel Gabriel appeared to Mary in Luke, Gabriel said, “Greetings, favored one! The Lord is with you.” Also, when Judas leaned in to betray Jesus with a kiss in Matthew, Judas said, “Greetings, Rabbi”. If I have done my homework correctly, I have just shared with you the only three times in the gospels that “greetings” occurs. The Greek word translates as “joy”. These three occurrences represent a formulaic use or expression that was a common form, even an informal greeting. Like “hi there” or “how’s it going”. On the one hand, these three “greetings” happen at pretty important moments in the gospels: the Annunciation, the Betrayal, and the Resurrection.” On the other hand, the Risen Jesus suddenly appears and uses an everyday, mundane, routine expression of greeting that seems a bit out of place, even underwhelming, after a great earthquake, a stone rolled back, a blinding angel, guards frightened out of their minds, and an empty tomb.

Like any grandparent, when a phone or an iPad in our house rings with a FaceTime chime, Cathy and I race to answer as quickly as we can. We run not with fear but great joy, we run great joy and greater joy. If I am being honest, most of the calls are at the instigation of soon-to-be four-year-old Franny, who wants to talk to Gram. You answer the call, and there isa screen full of Franny’s face as she holds the phone. Franny wants to talk to Gram about their respective cups of seeds growing and their gardens, soon to be planted. But last week, a FaceTime call came that warmed a grandfather’s heart. It was fifteen-month-old Maddie calling to talk to Pop. She was holding the phone, and all we could see was from her nose up. I could hear her smile, though. We exchanged the greeting I taught her. “Pop”, she says. I say “Haaay,” To which she says, “Haaaaay!” That was about it. That was all she wanted. She dropped the phone on the floor and ran off. That was about it but it was way more than enough!

The Risen Jesus appears to the frightened, joyful women on the run to go and tell the news. He suddenly appears and says “Haaay”. No don’t be afraid at first. He doesn’t call Mary by name like in the book of John. Here, after all the divine, bible-like special effects that one would expect to trumpet that first Easter morning, with the rolled away stone still within view, Jesus says “hi there, how’s it going, good morning, cheers mate, what’s up, hey there, yo.” A startling every day, informal, common greeting amid what was a far from everyday encounter. The women fall to his feet as both fear and great joy escalate. They take hold of his feet to try to somehow tell if he is real or not. The same feet the woman anointed with expensive perfume. The same feet that had been nailed to the cross. Jesus said to them, “Do not be afraid; go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me.”

In Matthew, the only appearance of the Risen Jesus beyond the fist bump with the two Marys somewhere near the tomb is in Galilee. The eleven disciples returned to Galilee, to the mountain to which Jesus had directed them. They saw him there, the Risen Jesus. The bible says, “They worshipped him, but some doubted.” That’s when Jesus gave the eleven the Great Commission. “All authority in heaven and earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

There’s not much else happening here at the end of Matthew in terms of resurrection. Oh, there are a few verses about the powers that be cobbling together a story about the disciples stealing the body. But in Matthew, not much else is going on after Easter morning except the Great Commission. No Emmaus Road; that’s in Luke. No breakfast on the beach; that’s in John. No Jesus putting Peter on the spot with, “Do you love me more than these?”; that’s John as well. It is as if Jesus’ ordinary greeting here in Matthew marks a shift away from the miraculous way the morning started and a shift toward an extraordinary promise of how resurrection power is unleashed in the world. “Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me.”

In Galilee. In Galilee is where Jesus called the disciples. It is where he taught. It’s where he ate with sinners and tax collectors. In Galilee is where he healed the sick. It’s where he fed the thousands with a couple loaves and fish. It’s where he told parables. It’s where he drove out demons. In Galilee is where he preached the Sermon on the Mount. It’s where the Pharisees and Sadducees first came to test him. It’s where he welcomed little children and challenged the rich young man by telling him to sell all his possessions, give the money to the poor and follow him.

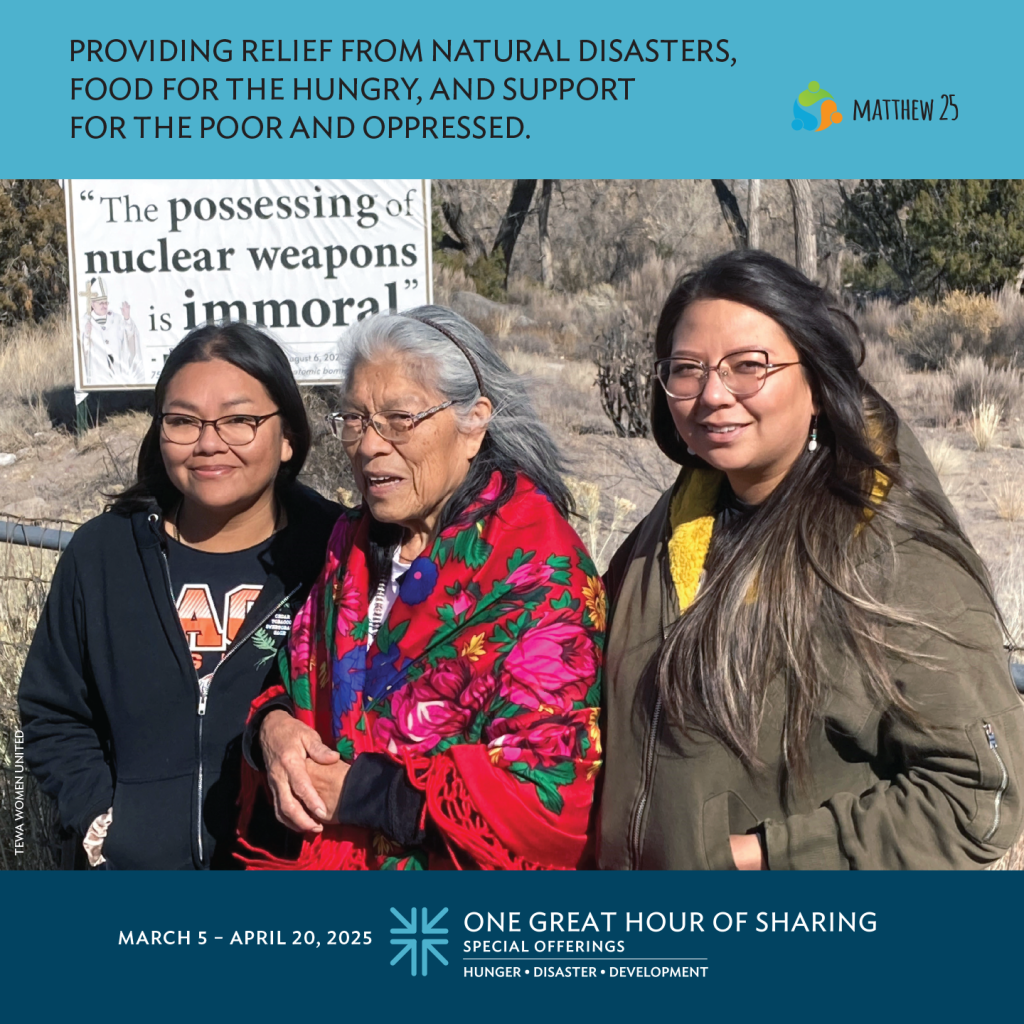

“He is going ahead of you to Galilee; there you will see him.” “Go to Galilee, they will see me there”, he said. In Galilee is where you will find my resurrection power unleashed. A resurrection life that comes not with trumpets blasting, or the earth shaking, or angels appearing, but with the poor being fed, and with the outcasts being served, and the unclean are embraced, with the first being last and the last being first, with turning the other cheek and loving one another, with the kingdom of God being taught, announced, proclaimed, served. In Galilee. In Galilee, there they will see me. An extraordinary understanding of how resurrection power is unleashed in the world.

I remember visiting a saint of the church years ago. I was a young pastor, nowhere near 30, young enough that he had been widowed longer than I had been alive. His name was Ray. He had his struggles when it came to health, but he explained that his father lived to be 102 so he didn’t expect to be going anywhere soon, though he wished the good the Lord would take him just like his wife, take him when he was sound asleep. “I’m ready anytime,” he said with a smile. His personal faith statement was as well-worn as the Apostles’ Creed itself.

Much of our conversation was about his worries and anxieties about life; his children, grandchildren, great children. He was worried about their marriages and jobs and challenges. He was worried about the economy and politics and the war in Iraq, and the Phillies who were in a slump. He wasn’t just complaining or being cranky. His worry was genuine. Then Ray used one of those clichés that are so often said, but his use had a weight to it. “David, I just don’t know what this world is coming to.” And he waved a hand like he was swatting a fly.

We all know I could have had that conversation yesterday. I’m sure I had little pastoral wisdom to offer back then for that saint who has long since gone to glory. Not sure how much I have now. But his faith statement and that weighty cliché of his, the assurance of his own spot next to the throne of grace and his angst about what this world’s coming to….they don’t match real well when it comes to the power of God’s resurrection promise. The promise of the resurrection power of Jesus Christ has been unleashed in the world now. Because the promise of the resurrection is for life eternal, yes! And it is also for the kingdom to come on earth as it is in heaven. “In my Father’s house are many mansions, I go to prepare a place for you…..and…Go to Galilee, you will see me there…I will be with you always”.

You may have read or heard of some conservative Christian pastors who have quite a following on social media. They embrace the evil of Christian nationalism. Recently, they began calling for an end to empathy. Here is one astonishing, heretical quote: “Empathy almost needs to be struck from the Christian vocabulary. Empathy is dangerous. Empathy is toxic. Empathy will align you with hell.” It is way past time for everyday preachers, disciples, congregations, denominations, for the Christian Church to respond in word and deed with “umm, hell no!

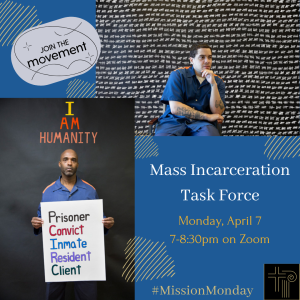

The followers of Jesus who listen and believe what Jesus taught us don’t have the luxury of basking in the piety of our Easter finery, or waiting for divine earthquakes or angel mic drops. Because the Risen Jesus is calling us to Galilee. The Risen Jesus yearns to say hello where the poor are being fed. The Risen Jesus is waiting to say “how’s it going” where the outcasts are being served. The Risen Jesus is saying “good morning” where the strangers are being welcomed and immigrants are protected, and international students are embraced. The Risen Jesus is shouting, “What’s up?” where acts of kindness and mercy carry the day. The Risen Jesus is hugging it out every time and every place where the people of God live resurrection power with the strength to love, the courage to do unto others as you would have them do unto you, and the bold resistance to love your neighbor as yourself. I have said it before from this pulpit, and I will keep saying it louder and louder. In the most difficult of seasons of life, the simplest parts of the gospel of Jesus Christ become all the more compelling, essential, and true.

Christ is Risen! He is Risen Indeed! Keep the strength to love.

Christ is Risen! He is Risen Indeed! Don’t lose the courage to do unto others as you would have them to unto you!

Christ is Risen! He is Risen Indeed! Live the bold, resistant to love your neighbor as yourself.

Christ is Risen! He is Risen Indeed!